Sometimes 225 words just aren't enough. Further panning what needs to be panned further: In The Studio With Martin Hannett is a Joy Division legacy cash-grab that would make even Tony Wilson blush. Martin Hannett madness imagery is so threadbare it's nearly see-through; putting him in that pantheon of gone-crackers producers like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson is a sin against laziness. Even worse: Because Hannett was eccentric and daft and constantly making drummers take their kits apart for noise that only he heard!, we're led to believe his studio offcuts and engineering experiments are, I don't know, important to clutch and study. Sure, there's an alternate version of "Digital" that's so obviously Mancunian in the way it sounds recorded from the other end of a crumbling, red-brick railroad tunnel. And there's another track where Hannett noodles around with the broken glass we recall from "I Remember Nothing." But these aren't so much highlights, as much as they're mildly interesting, one-off material amid track after track of relative dross. In The Studio With Martin Hannett was touted as one of the most important Joy Division discoveries ever, which only leads me to believe that there's a special ring in Hell for label publicists.

Sometimes 225 words just aren't enough. Further panning what needs to be panned further: In The Studio With Martin Hannett is a Joy Division legacy cash-grab that would make even Tony Wilson blush. Martin Hannett madness imagery is so threadbare it's nearly see-through; putting him in that pantheon of gone-crackers producers like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson is a sin against laziness. Even worse: Because Hannett was eccentric and daft and constantly making drummers take their kits apart for noise that only he heard!, we're led to believe his studio offcuts and engineering experiments are, I don't know, important to clutch and study. Sure, there's an alternate version of "Digital" that's so obviously Mancunian in the way it sounds recorded from the other end of a crumbling, red-brick railroad tunnel. And there's another track where Hannett noodles around with the broken glass we recall from "I Remember Nothing." But these aren't so much highlights, as much as they're mildly interesting, one-off material amid track after track of relative dross. In The Studio With Martin Hannett was touted as one of the most important Joy Division discoveries ever, which only leads me to believe that there's a special ring in Hell for label publicists.

Wednesday, August 20, 2008

Sometimes 225 words just aren't enough. Further panning what needs to be panned further: In The Studio With Martin Hannett is a Joy Division legacy cash-grab that would make even Tony Wilson blush. Martin Hannett madness imagery is so threadbare it's nearly see-through; putting him in that pantheon of gone-crackers producers like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson is a sin against laziness. Even worse: Because Hannett was eccentric and daft and constantly making drummers take their kits apart for noise that only he heard!, we're led to believe his studio offcuts and engineering experiments are, I don't know, important to clutch and study. Sure, there's an alternate version of "Digital" that's so obviously Mancunian in the way it sounds recorded from the other end of a crumbling, red-brick railroad tunnel. And there's another track where Hannett noodles around with the broken glass we recall from "I Remember Nothing." But these aren't so much highlights, as much as they're mildly interesting, one-off material amid track after track of relative dross. In The Studio With Martin Hannett was touted as one of the most important Joy Division discoveries ever, which only leads me to believe that there's a special ring in Hell for label publicists.

Sometimes 225 words just aren't enough. Further panning what needs to be panned further: In The Studio With Martin Hannett is a Joy Division legacy cash-grab that would make even Tony Wilson blush. Martin Hannett madness imagery is so threadbare it's nearly see-through; putting him in that pantheon of gone-crackers producers like Phil Spector and Brian Wilson is a sin against laziness. Even worse: Because Hannett was eccentric and daft and constantly making drummers take their kits apart for noise that only he heard!, we're led to believe his studio offcuts and engineering experiments are, I don't know, important to clutch and study. Sure, there's an alternate version of "Digital" that's so obviously Mancunian in the way it sounds recorded from the other end of a crumbling, red-brick railroad tunnel. And there's another track where Hannett noodles around with the broken glass we recall from "I Remember Nothing." But these aren't so much highlights, as much as they're mildly interesting, one-off material amid track after track of relative dross. In The Studio With Martin Hannett was touted as one of the most important Joy Division discoveries ever, which only leads me to believe that there's a special ring in Hell for label publicists.

Tuesday, August 19, 2008

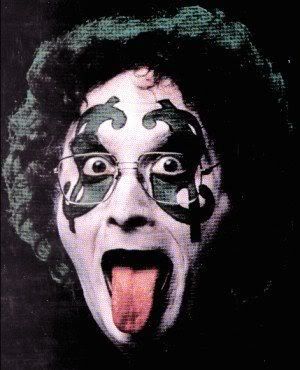

You post a picture and attach very few words to it because you're undeniably lazy, or because the boss is extra demanding today, or because you've spent too much time weighing the merits of your nattily trimmed beard. But sometimes pictures need very few words, or in more rare cases, no words at all. And so you go searching for said pictures, partly intent on covering up your laziness, industriousness, beardiness, etc., but mostly intent on delivering some sort of bold pronouncement your words aren't qualified to make. This is one of those pictures. One night I listened to "Atmosphere" and stared at this photo, splashed across Paul Morley's book, and wondered if the step ladder needed to change the industrial bulbs in that dank tunnel would have been tall enough to tie a proper rope for a hanging. I often feel like only the most morbid of queries haunt the curious. Ian also pondered this in my company, but only after I had turned him off and gone to bed.

You post a picture and attach very few words to it because you're undeniably lazy, or because the boss is extra demanding today, or because you've spent too much time weighing the merits of your nattily trimmed beard. But sometimes pictures need very few words, or in more rare cases, no words at all. And so you go searching for said pictures, partly intent on covering up your laziness, industriousness, beardiness, etc., but mostly intent on delivering some sort of bold pronouncement your words aren't qualified to make. This is one of those pictures. One night I listened to "Atmosphere" and stared at this photo, splashed across Paul Morley's book, and wondered if the step ladder needed to change the industrial bulbs in that dank tunnel would have been tall enough to tie a proper rope for a hanging. I often feel like only the most morbid of queries haunt the curious. Ian also pondered this in my company, but only after I had turned him off and gone to bed.

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

"I suppose I was about twelve years old. We used to go to a place called Ballystockart to fish. We stopped in the village on the way up to this place and I went to this little stone house, and there was an old man there with dark weather-beaten skin, and we asked him if he had any water. He gave us some water which he said he'd got from the stream. We drank some and everything seemed to stop for me. Time stood still. For five minutes everything was really quiet and I was in this 'other dimension.' That's what the song is about."

"I suppose I was about twelve years old. We used to go to a place called Ballystockart to fish. We stopped in the village on the way up to this place and I went to this little stone house, and there was an old man there with dark weather-beaten skin, and we asked him if he had any water. He gave us some water which he said he'd got from the stream. We drank some and everything seemed to stop for me. Time stood still. For five minutes everything was really quiet and I was in this 'other dimension.' That's what the song is about.""And it stoned me to my soul / Stoned me just like jelly roll."

You don't take Bear Notch Road . . . (wait for it, Yakov) . . . it takes you. While the idling SUVs with green canoes strapped to the roofs teemed with unbuckled impatience, I hugged corners and my elation. But I didn't share my secret; while companions inched behind consumers, I drank local beer and debated internally whether Van forges stronger bonds while one is grounded or in transit. And we were all better for it.

Wednesday, July 23, 2008

Randy Newman's "A Few Words in Defense of Our Country" contains the first eight bars of "Columbia, The Gem of the Ocean." Newman inserts a snippet of this sentimental, patriotic ballad to remind us all of what makes America rather swell and why we should tune into the Republican National Convention in a few weeks. It's all pretty sly: Like previous Newman efforts, "A Few Words in Defense of Our Country" is a trifle critical of the United States. One could lift some of the song's more forceful lines and drop them into the dialogue bubble of a political cartoon. "Now it seems like we're supposed to be afraid / It's patriotic in fact and color coded." "The end of an empire is messy at best / And this empire is ending."

Randy Newman's "A Few Words in Defense of Our Country" contains the first eight bars of "Columbia, The Gem of the Ocean." Newman inserts a snippet of this sentimental, patriotic ballad to remind us all of what makes America rather swell and why we should tune into the Republican National Convention in a few weeks. It's all pretty sly: Like previous Newman efforts, "A Few Words in Defense of Our Country" is a trifle critical of the United States. One could lift some of the song's more forceful lines and drop them into the dialogue bubble of a political cartoon. "Now it seems like we're supposed to be afraid / It's patriotic in fact and color coded." "The end of an empire is messy at best / And this empire is ending."Newman says he isn't fond of penning "Tom Lehrer-like songs" because being too topical and timely means you date your material. But it's rather fun to skim backwards and re-visit albums like Sail Away, and realize his political rhetoric hasn't changed much in 30 years because the political landscape hasn't changed much in 30 years. I suppose that same sense of eternalness is what makes Newman such a qualified candidate to speak on what reeks politically. He went Disneying, but returned without a pair of mouse ears. He won an Academy Award and melted the trophy down for the revolution's bullets. He hasn't changed much either.

Friday, July 18, 2008

When I glance at this album cover, I often think the gentleman is holding a rifle. Quite possibly it's because what little I've read of Nigerian history is typically blood-soaked: pogroms, coups, civil war. According to director Ruggero Deodato, the mini-documentary featured in the horror cult classic Cannibal Holocasut consists of actual firing-squad footage from Nigeria. Men, women, and children are shown being executed.

When I glance at this album cover, I often think the gentleman is holding a rifle. Quite possibly it's because what little I've read of Nigerian history is typically blood-soaked: pogroms, coups, civil war. According to director Ruggero Deodato, the mini-documentary featured in the horror cult classic Cannibal Holocasut consists of actual firing-squad footage from Nigeria. Men, women, and children are shown being executed. Of course, this is just a tiny, dark chapter in Nigeria's history. Lagos' status as an ever-bloated mega-city -- a place likely on the precipice of some urban/eco disaster -- is what garners much attention today: It's depicted rather vibrantly in George Packer's New Yorker piece on the former Nigerian capital: "In many African cities, there is an oppressive atmosphere of people lying about in the middle of the day, of idleness sinking into despair. In Lagos, everyone is a striver."

I've read how the period between the end of the Nigerian Civil War in 1970 and the military coup in 1975 was a golden age for Nigerian music, particularly in Lagos. From a May issue of The Guardian: "The country's oil boom briefly promised to bring prosperity. Many middle-class Nigerians were travelling and studying abroad, appetite for rock music was growing and British labels EMI and Decca saw a fertile market."

And then: "By the time [EMI producer Odion] Iruoje left EMI in 1978, the good times were already over. As oil money was siphoned off by corrupt politicians, crime and unemployment rose. The 7in single market dried up. Bands who once earned a crust playing hotels and clubs were squeezed out by singers with cheap synthesisers. Most groups split out of frustration. 'Berkley Jones, the guitarist for BLO, is now a property developer,' said Soundway's Miles Cleret. 'He hasn't picked up a guitar in 10 years and yet he was one of the most talented guitarists in Lagos. He was a pin-up -- a real star.'"

Despite such a tumultuous fall, Packer's piece describes the immediate, visceral power Nigerian music still has upon newcomers. Fifteen million strong now -- more squalid, more dangerous, more competitive, more desperate. In Lagos, there are still good times to be had. "Upon arriving in the city, he went to a club that played juju -- pop music infused with Yoruba rhythms -- and stayed out until two in the morning. 'This experience alone makes me believe I have a new life living now,' he said, in English, the lingua franca of Lagos. 'All the time, you see crowds everywhere. I was motivated by that. In the village, you're not free at all, and whatever you're going to do today you'll do tomorrow.'"

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)